Guests in the Field

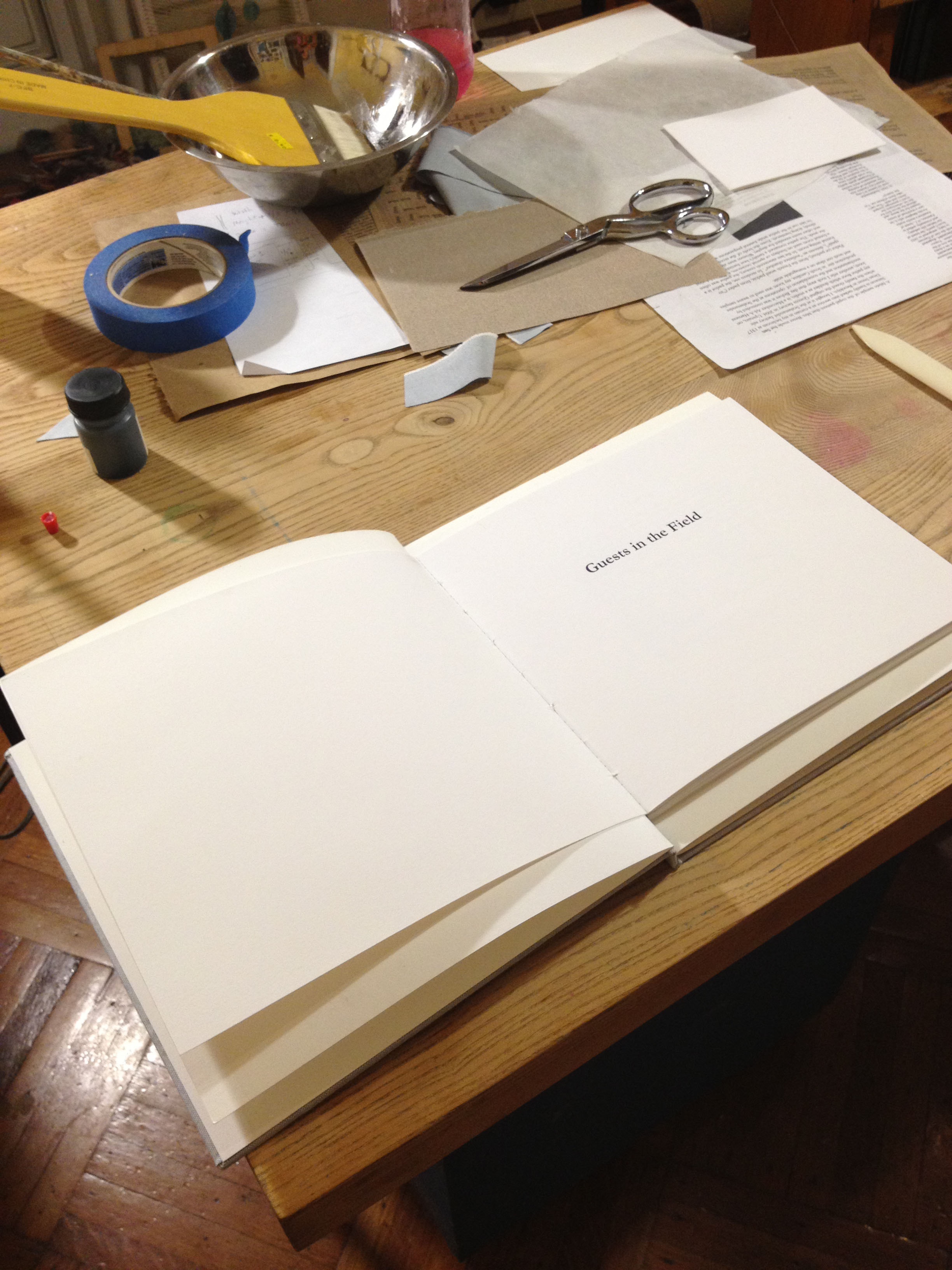

Guests in the Field is an invitation to artists of any media with no weaving experience to make a cloth on the 8-harness floor loom in my studio. The following are the steps for participants:

1. Read the Guests in the Field Users Manual.

2. Meet with Kristine to discuss ideas, weave structure and materials and to set a date for weaving.

3. Weave an 18x19 inch cloth.

In the 21st century weaving is both vernacular and peculiar. Although woven cloth is second nature to us from a use perspective, at the level of production weaving is unfamiliar to most people. It is exactly this likelihood that underlays Guests in the Field. When artists use an unfamiliar technology the strangeness of the new and the residue of the familiar combine to become material for form. Decision making, process, resolution, attention and all the effects of habit are in relief against the particularities of the new technology. There are also pleasures and frustrations when working on a new apparatus. Encounters with new pleasures and frustrations change the way we make things. I am interested in all of this. Alone in the studio I naturally wonder how other artists arrive at the subtle and illusive moves that determine their work. Guests in the Field arises from this curiosity.

continued below...

Marina Ancona

Laurel Sparks

Lan Thao Lam

Jennifer Wallace

Janice Guy

Fabienne Lasserre

Benny Merris

David East

continued...

Artists work by method. Decisions may happen by design and execution or by chance. A cloth can be woven entirely by improvisation or produced by a system of response to outside factors: the news, a human collaborator, weather. Copying is a compelling method. Inevitably, methods that artists already use in other media will translate into weaving decisions and possibly vice versa.

All weavings made as part of Guests in the Field will have two consistent components, scale and warp material. Weavings will be 18x19 inches. The orientation will be determined in the dressing of the loom but the cloth can be rotated after it’s finished. In the middle of this manual is a fold-out practical of these dimensions. We are using a linen warp in two possible weights. Linen fibers—made from flax—are long and, therefore, strong and less elastic than other fibers. The linen can be used in its natural color or dyed or both.

Individual weavers will determine the remaining components of their weaving. Things to consider are weave structure, materials, color, conceptual decision-making and schedule. Basic weave structures are addressed in this manual. Information about plain weave, tapestry, twill and double cloth is included as these are fundamental, easily within the technical reach of a first-time weaver and can be used in combination with each other. All weaves are the result of experimentation and weavers may find that they prefer to manipulate threads and invent their cloth as they weave.

Any materials that can be rendered linear or held in a linear web are viable for weaving. Color can be introduced in the warp or the weft or both and will be visible relative to the structure of the weave. In tapestry, for example, the warp is largely covered leaving the weft colors highly legible. In a balanced weave, the colors of the warp and weft will mix. Threads in a range of colors can be purchased or dyed for you. Less traditional materials that you may use will bear their own color or, in some cases, can be dyed or stained. Paper, for example, can be made into a linear element conducive to use as weft. Its color may be changed before it is woven. Finished weavings, once they are off the loom, may also be dyed, painted, printed, etc.

Complexity of pattern and the scale of materials will largely determine the number of hours required to complete a weaving. It is feasible that a cloth of the dimensions chosen for this project could be woven in a day. Alternately, the weaving might require many days. As Guests in the Field has only one loom at its disposal, weavers should not plan to spend more than a couple of weeks on their cloth. To date, weavers have typically spent 2 or 3 days. Some weaver’s schedules may limit weaving to evening hours or weekends. These time constraints do not preclude participation in Guests in the Field.

Participating weavers will be relieved of some of the technical and labor-intensive aspects of weaving. Winding the warp and dressing the loom are generally considered to be the more onerous aspects of the weaving process. I will make the calculations and dress the loom for you according to the specs of your cloth arrived at through discussion and using the information in this manual.

Woven cloth has been used as shelter, clothing, currency and ritual object and has performed myriad human needs since the Paleolithic era. These varied uses of woven cloth are possible because weave structure can accommodate any material that can be rendered linear or held in a linear web. The fine filaments of surgical cloth embedded with electrical impulses and microchips have the same components as woven steel with architectural load-bearing capacities.

Although the distribution of the labor required for the tasks of weaving differs between communities and changes over time, weaving has always and everywhere been a shared activity. In Ghana, where weaving probably started around 3200 B.C., men wove the long strips for Kente cloth using thread spun by women who then sewed the strips together. In colonial New England it was common for more skilled weavers, a neighbor perhaps, to warp or dress the loom for less experienced weavers who would then throw the shuttle, treadle according to pattern and finish the cloth.

The width of medieval and early European looms was determined by how far the weaver could throw and catch the shuttle from one side of the cloth to another. English broadlooms had a similar construction but were twice as wide and therefore required two weavers working together. The term ‘broadcloth’ derives from these looms and refers to cloth that is woven at the full width of the loom. Historically and in production sites that are currently using pre-industrial practices, it is common for many people to sit next to each other and work on one cloth simultaneously. In the case of large carpets, for example, it would be nearly impossible for one weaver to finish in a reasonable amount of time. Skills and patterns were learned this way. Patterns that persist over long periods of time—hundreds of years, in some cases—are usually learned by observation and recorded only by the cloth itself. Passing patterns between generations of weavers in this way produces cloths marked by the specificity of bodies and an accumulation of haptic and kinesthetic translations over time.

It may be weaving's history as a shared activity and its grid structure that have persistently held it in an underprivileged relation to objects whose form is made by one body and are considered a cipher for the subject, a mark of individuality. This distinction mirrors the distinction that the art historical canon has used to privilege certain objects as art while others remain in contested territory.

Guests in the Field welcomes collaborations...